A guide to logging in Python

Logging is a critical way to understand what's going on inside an application.

There is little worse as a developer than trying to figure out why an application is not working if you don't know what is going on inside it. Sometimes you can't even tell whether the system is working as designed at all.

When applications are running in production, they become black boxes that need to be traced and monitored. One of the simplest, yet most important ways to do so is by logging. Logging allows us—at the time we develop our software—to instruct the program to emit information while the system is running that will be useful for us and our sysadmins.

More Python Resources

- What is Python?

- Top Python IDEs

- Top Python GUI frameworks

- Latest Python content

- More developer resources

The same way we document code for future developers, we should direct new software to generate adequate logs for developers and sysadmins. Logs are a critical part of the system documentation about an application's runtime status. When instrumenting your software with logs, think it like writing documentation for developers and sysadmins who will maintain the system in the future.

Some purists argue that a disciplined developer who uses logging and testing should hardly need an interactive debugger. If we cannot reason about our application during development with verbose logging, it will be even harder to do it when our code is running in production.

This article looks at Python's logging module, its design, and ways to adapt it for more complex use cases. This is not intended as documentation for developers, rather as a guide to show how the Python logging module is built and to encourage the curious to delve deeper.

Why use the logging module?

A developer might argue, why aren't simple print statements sufficient? The loggingmodule offers multiple benefits, including:

- Multi-threading support

- Categorization via different levels of logging

- Flexibility and configurability

- Separation of the how from the what

This last point, the actual separation of the what we log from the how we log enables collaboration between different parts of the software. As an example, it allows the developer of a framework or library to add logs and let the sysadmin or person in charge of the runtime configuration decide what should be logged at a later point.

What's in the logging module

The logging module beautifully separates the responsibility of each of its parts (following the Apache Log4j API's approach). Let's look at how a log line travels around the module's code and explore its different parts.

Logger

Loggers are the objects a developer usually interacts with. They are the main APIs that indicate what we want to log.

Given an instance of a logger, we can categorize and ask for messages to be emitted without worrying about how or where they will be emitted.

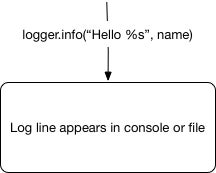

For example, when we write logger.info("Stock was sold at %s", price) we have the following model in mind:

1-ikkitaj.jpg

We request a line and we assume some code is executed in the logger that makes that line appear in the console/file. But what actually is happening inside?

Log records

Log records are packages that the logging module uses to pass all required information around. They contain information about the function where the log was requested, the string that was passed, arguments, call stack information, etc.

These are the objects that are being logged. Every time we invoke our loggers, we are creating instances of these objects. But how do objects like these get serialized into a stream? Via handlers!

Handlers

Handlers emit the log records into any output. They take log records and handle them in the function of what they were built for.

As an example, a FileHandler will take a log record and append it to a file.

The standard logging module already comes with multiple built-in handlers like:

- Multiple file handlers (TimeRotated, SizeRotated, Watched) that can write to files

- StreamHandler can target a stream like stdout or stderr

- SMTPHandler sends log records via email

- SocketHandler sends LogRecords to a streaming socket

- SyslogHandler, NTEventHandler, HTTPHandler, MemoryHandler, and others

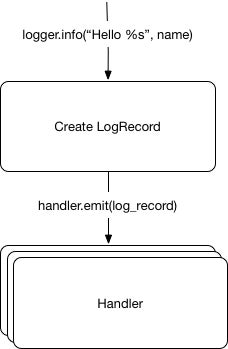

We have now a model that's closer to reality:

2-crmvrmf.jpg

But most handlers work with simple strings (SMTPHandler, FileHandler, etc.), so you may be wondering how those structured LogRecords are transformed into easy-to-serialize bytes…

Formatters

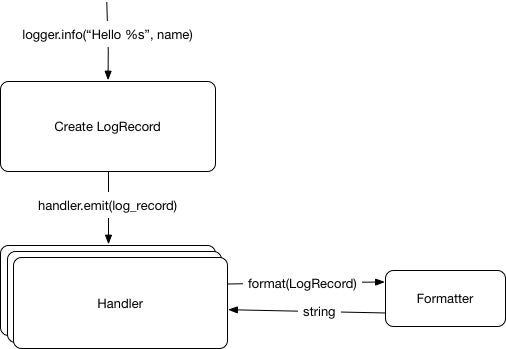

Let me present the Formatters. Formatters are in charge of serializing the metadata-rich LogRecord into a string. There is a default formatter if none is provided.

The generic formatter class provided by the logging library takes a template and style as input. Then placeholders can be declared for all the attributes in a LogRecordobject.

As an example: '%(asctime)s %(levelname)s %(name)s: %(message)s' will generate logs like 2017-07-19 15:31:13,942 INFO parent.child: Hello EuroPython.

Note that the attribute message is the result of interpolating the log's original template with the arguments provided. (e.g., for logger.info("Hello %s", "Laszlo"), the message will be "Hello Laszlo").

All default attributes can be found in the logging documentation.

OK, now that we know about formatters, our model has changed again:

3-olzyr7p.jpg

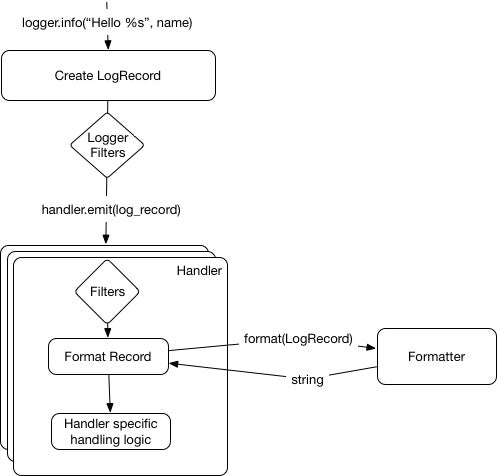

Filters

The last objects in our logging toolkit are filters.

Filters allow for finer-grained control of which logs should be emitted. Multiple filters can be attached to both loggers and handlers. For a log to be emitted, all filters should allow the record to pass.

Users can declare their own filters as objects using a filter method that takes a record as input and returns True/False as output.

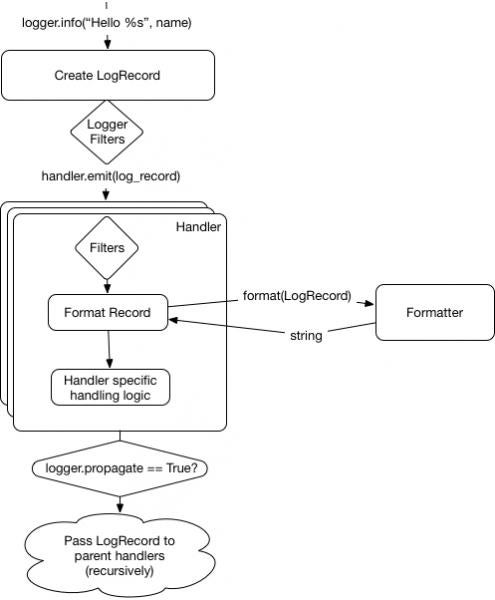

With this in mind, here is the current logging workflow:

4-nfjk7uc.jpg

The logger hierarchy

At this point, you might be impressed by the amount of complexity and configuration that the module is hiding so nicely for you, but there is even more to consider: the logger hierarchy.

We can create a logger via logging.getLogger(<logger_name>). The string passed as an argument to getLogger can define a hierarchy by separating the elements using dots.

As an example, logging.getLogger("parent.child") will create a logger "child" with a parent logger named "parent." Loggers are global objects managed by the logging module, so they can be retrieved conveniently anywhere during our project.

Logger instances are also known as channels. The hierarchy allows the developer to define the channels and their hierarchy.

After the log record has been passed to all the handlers within the logger, the parents' handlers will be called recursively until we reach the top logger (defined as an empty string) or a logger has configured propagate = False. We can see it in the updated diagram:

5-sjkrpt3.jpg

Note that the parent logger is not called, only its handlers. This means that filters and other code in the logger class won't be executed on the parents. This is a common pitfall when adding filters to loggers.

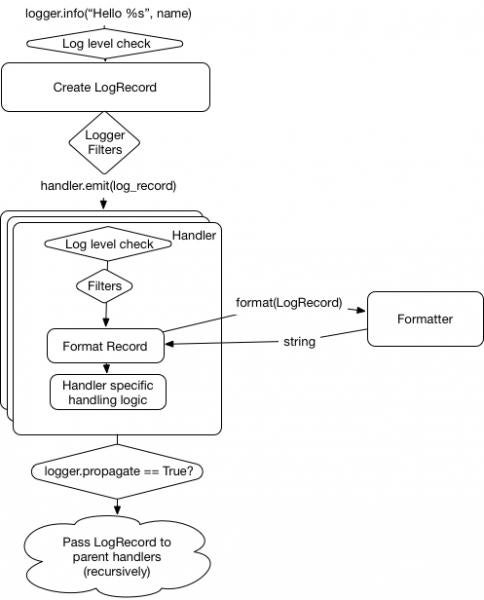

Recapping the workflow

We've examined the split in responsibility and how we can fine tune log filtering. But there are two other attributes we haven't mentioned yet:

- Loggers can be disabled, thereby not allowing any record to be emitted from them.

- An effective level can be configured in both loggers and handlers.

As an example, when a logger has configured a level of INFO, only INFO levels and above will be passed. The same rule applies to handlers.

With all this in mind, the final flow diagram in the logging documentation looks like this:

6-kd6eiyr.jpg

How to use logging

Now that we've looked at the logging module's parts and design, it's time to examine how a developer interacts with it. Here is a code example:

import logging

def sample_function(secret_parameter):

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__) # __name__=projectA.moduleB

logger.debug("Going to perform magic with '%s'", secret_parameter)

…

try:

result = do_magic(secret_parameter)

except IndexError:

logger.exception("OMG it happened again, someone please tell Laszlo")

except:

logger.info("Unexpected exception", exc_info=True)

raise

else:

logger.info("Magic with '%s' resulted in '%s'", secret_parameter, result, stack_info=True)

This creates a logger using the module __name__. It will create channels and hierarchies based on the project structure, as Python modules are concatenated with dots.

The logger variable references the logger "module," having "projectA" as a parent, which has "root" as its parent.

On line 5, we see how to perform calls to emit logs. We can use one of the methods debug, info, error, or critical to log using the appropriate level.

When logging a message, in addition to the template arguments, we can pass keyword arguments with specific meaning. The most interesting are exc_info and stack_info. These will add information about the current exception and the stack frame, respectively. For convenience, a method exception is available in the logger objects, which is the same as calling error with exc_info=True.

These are the basics of how to use the logger module. ʘ‿ʘ. But it is also worth mentioning some uses that are usually considered bad practices.

Greedy string formatting

Using loggger.info("string template {}".format(argument)) should be avoided whenever possible in favor of logger.info("string template %s", argument). This is a better practice, as the actual string interpolation will be used only if the log will be emitted. Not doing so can lead to wasted cycles when we are logging on a level over INFO, as the interpolation will still occur.

Capturing and formatting exceptions

Quite often, we want to log information about the exception in a catch block, and it might feel intuitive to use:

try:

…

except Exception as error:

logger.info("Something bad happened: %s", error)

But that code can give us log lines like Something bad happened: "secret_key." This is not that useful. If we use exc_info as illustrated previously, it will produce the following:

try:

…

except Exception:

logger.info("Something bad happened", exc_info=True)

Something bad happened

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "sample_project.py", line 10, in code

inner_code()

File "sample_project.py", line 6, in inner_code

x = data[“secret_key”]

KeyError: 'secret_key'

This not only contains the exact source of the exception, but also the type.

Configuring our loggers

It's easy to instrument our software, and we need to configure the logging stack and specify how those records will be emitted.

There are multiple ways to configure the logging stack.

BasicConfig

This is by far the simplest way to configure logging. Just doing logging.basicConfig(level="INFO") sets up a basic StreamHandler that will log everything on the INFO and above levels to the console. There are arguments to customize this basic configuration. Some of them are:

| Format | Description | Example |

| filename | Specifies that a FileHandler should be created, using the specified filename, rather than a StreamHandler | /var/logs/logs.txt |

| format | Use the specified format string for the handler | "'%(asctime)s %(message)s'" |

| datefmt | Use the specified date/time format | "%H:%M:%S" |

| level | Set the root logger level to the specified level | "INFO" |

This is a simple and practical way to configure small scripts.

Note, basicConfig only works the first time it is called in a runtime. If you have already configured your root logger, calling basicConfig will have no effect.

DictConfig

The configuration for all elements and how to connect them can be specified as a dictionary. This dictionary should have different sections for loggers, handlers, formatters, and some basic global parameters.

Here's an example:

config = {

'disable_existing_loggers': False,

'version': 1,

'formatters': {

'short': {

'format': '%(asctime)s %(levelname)s %(name)s: %(message)s'

},

},

'handlers': {

'console': {

'level': 'INFO',

'formatter': 'short',

'class': 'logging.StreamHandler',

},

},

'loggers': {

'': {

'handlers': [‘console’],

'level': 'ERROR',

},

'plugins': {

'handlers': [‘console’],

'level': 'INFO',

'propagate': False

}

},

}

import logging.config

logging.config.dictConfig(config)

When invoked, dictConfig will disable all existing loggers, unless disable_existing_loggers is set to false. This is usually desired, as many modules declare a global logger that will be instantiated at import time, before dictConfig is called.

You can see the schema that can be used for the dictConfig method. Often, this configuration is stored in a YAML file and configured from there. Many developers often prefer this over using fileConfig, as it offers better support for customization.

Extending logging

Thanks to the way it is designed, it is easy to extend the logging module. Let's see some examples:

Logging JSON

If we want, we can log JSON by creating a custom formatter that transforms the log records into a JSON-encoded string:

import logging

import logging.config

import json

ATTR_TO_JSON = [‘created’, ‘filename’, ‘funcName’, ‘levelname’, ‘lineno’, ‘module’, ‘msecs’, ‘msg’, ‘name’, ‘pathname’, ‘process’, ‘processName’, ‘relativeCreated’, ‘thread’, ‘threadName’]

class JsonFormatter:

def format(self, record):

obj = {attr: getattr(record, attr)

for attr in ATTR_TO_JSON}

return json.dumps(obj, indent=4)

handler = logging.StreamHandler()

handler.formatter = JsonFormatter()

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.addHandler(handler)

logger.error("Hello")

Adding further context

On the formatters, we can specify any log record attribute.

We can inject attributes in multiple ways. In this example, we abuse filters to enrich the records.

import logging

import logging.config

GLOBAL_STUFF = 1

class ContextFilter(logging.Filter):

def filter(self, record):

global GLOBAL_STUFF

GLOBAL_STUFF += 1

record.global_data = GLOBAL_STUFF

return True

handler = logging.StreamHandler()

handler.formatter = logging.Formatter("%(global_data)s %(message)s")

handler.addFilter(ContextFilter())

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.addHandler(handler)

logger.error("Hi1")

logger.error("Hi2")

This effectively adds an attribute to all the records that go through that logger. The formatter will then include it in the log line.

Note that this impacts all log records in your application, including libraries or other frameworks that you might be using and for which you are emitting logs. It can be used to log things like a unique request ID on all log lines to track requests or to add extra contextual information.

Starting with Python 3.2, you can use setLogRecordFactory to capture all log record creation and inject extra information. The extra attribute and the LoggerAdapter classmay also be of the interest.

Buffering logs

Sometimes we would like to have access to debug logs when an error happens. This is feasible by creating a buffered handler that will log the last debug messages after an error occurs. See the following code as a non-curated example:

import logging

import logging.handlers

class SmartBufferHandler(logging.handlers.MemoryHandler):

def __init__(self, num_buffered, *args, **kwargs):

kwargs[“capacity”] = num_buffered + 2 # +2 one for current, one for prepop

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

def emit(self, record):

if len(self.buffer) == self.capacity – 1:

self.buffer.pop(0)

super().emit(record)

handler = SmartBufferHandler(num_buffered=2, target=logging.StreamHandler(), flushLevel=logging.ERROR)

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

logger.setLevel("DEBUG")

logger.addHandler(handler)

logger.error("Hello1")

logger.debug("Hello2") # This line won't be logged

logger.debug("Hello3")

logger.debug("Hello4")

logger.error("Hello5") # As error will flush the buffered logs, the two last debugs will be logged

For more information

This introduction to the logging library's flexibility and configurability aims to demonstrate the beauty of how its design splits concerns. It also offers a solid foundation for anyone interested in a deeper dive into the logging documentation and the how-to guide. Although this article isn't a comprehensive guide to Python logging, here are answers to a few frequently asked questions.

My library emits a "no logger configured" warning

Check how to configure logging in a library from "The Hitchhiker's Guide to Python."

What happens if a logger has no level configured?

The effective level of the logger will then be defined recursively by its parents.

All my logs are in local time. How do I log in UTC?

Formatters are the answer! You need to set the converter attribute of your formatter to generate UTC times. Use converter = time.gmtime.